Establishing a safe FSM system - an endeavour filled with uncertainty and risks

Incredibly, even the most remote village in the mountains of Jumla district in Nepal has a toilet. This is the success of the country’s proud, non-subsidized sanitation movement that has convinced people of the importance of building and using a toilet. Walking through Chandannath municipality however, the headquarters of the district, I pass by a community toilet block that serves as the only toilet for a dense settlement of about 100 households, because there is not enough land for individual household toilets.

People are worried. The toilet may soon close. They hear that the soakage pit attached to the toilet is filling up, but there are no services that the management committee can call to empty out the faecal sludge that accumulates in the pit. Secretly, some households in other parts of the town have already emptied out their pits manually at night and dumped the sludge in the drainage channel or in the river. The smell that permeated from the channel the next day, however, soon caused many complaints from their neighbours. Managing faecal sludge safely from toilets is fast becoming the next big challenge for a country that is on the verge of achieving universal sanitation coverage.

Through our urban sanitation and hygiene initiatives in Nepal, we aim to support small towns like Chandannath municipality (population 10,000) to develop services for faecal sludge management (FSM) that townspeople can rely on to safely empty their pits, transport the waste, and treat or dispose it properly. It is an endeavour filled with uncertainty and risks. How to establish a service where none exists? How to ensure that if a service starts people will pay for it? How to convince a municipality which considers FSM a "non-issue" that they are responsible for ensuring such services for the town?

Fortunately in Jumla, we have found an in-road to addressing these challenges - the Chamber of Commerce and Industries of Jumla (JCCI). This is a highly active body of like-minded entrepreneurs with strong leadership which is involved in various activities that seek to solve public problems, develop economic opportunities, and make their town a better place. The JCCI also has a lot of clout - people listen to them, they regularly engage political groups in constructive dialogue for development, and they work on motivating government stakeholders to improve services. The JCCI is keen to develop and operate a faecal sludge collection and disposal service as a social enterprise.

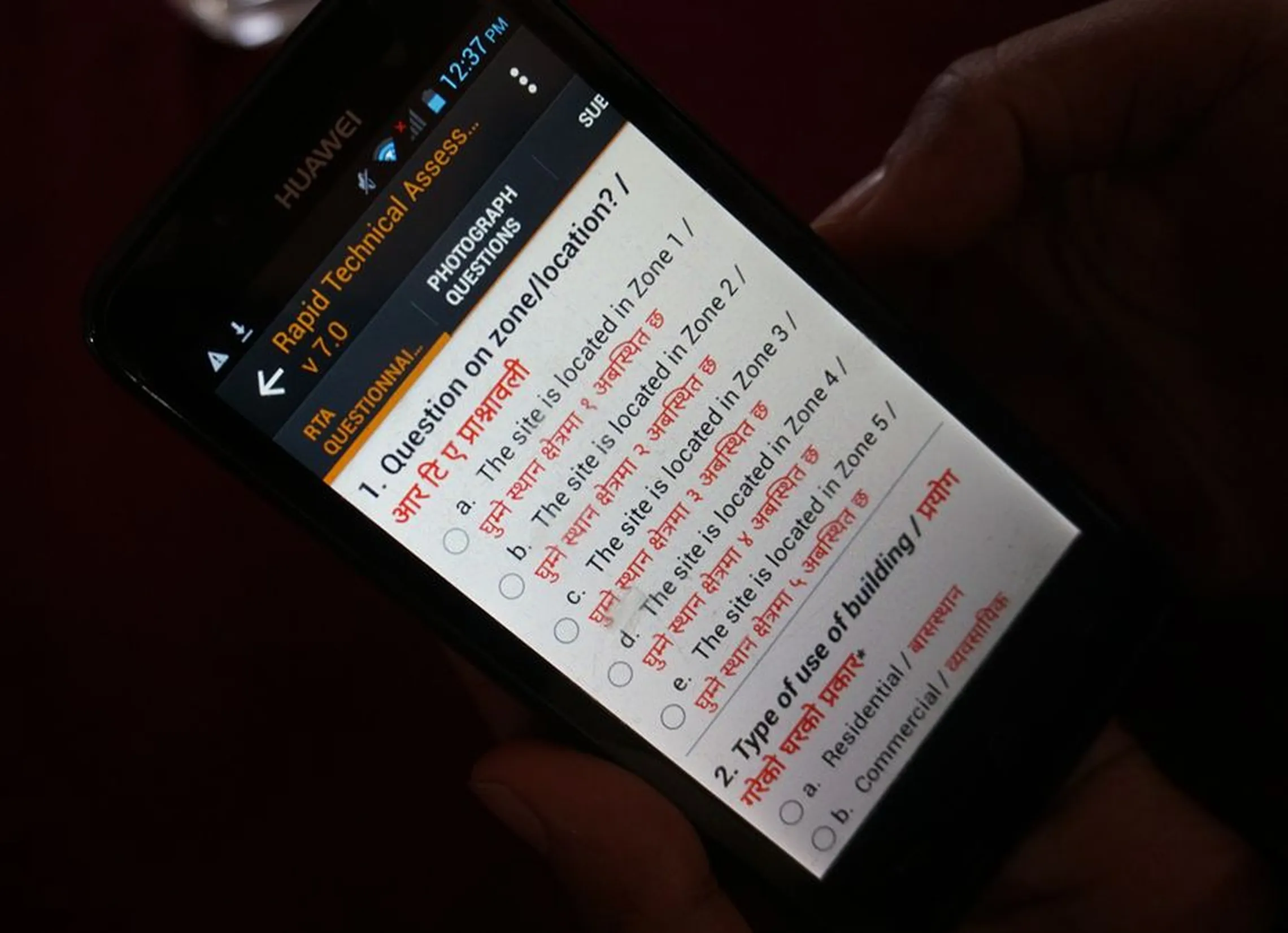

Building on this thread, we have mapped out a series of steps to provide a systematic way for developing and sustaining FSM services in Chandannath municipality. Together with the municipality, JCCI, and water supply office staff, we first conducted a "rapid technical assessment" using mobile phones to understand the faecal sludge volumes produced and plan for the service infrastructure that would be needed (size and type of desludging equipment, land area for treatment or disposal, etc). This was followed by formative research to understand which factors help create a willingness to take-up services and identify effective communication channels about upcoming services for the public. One family in the research commented, "We want to empty out the pit regularly because we don’t have the waste resources (time and money) to build another one". Furthermore, those who had already emptied out their pit were not comfortable with having had to throw their sludge in the river. The research has also shown that if services are available, the townspeople are ready to pay as per charges established by the municipality.

Using mobile phones to collect data for RTA

The data collection was the easy part. Next steps are to design an effective business model, establish the service infrastructure and ensure uptake and payment of services through communications and enforcement. From initial analyses of data and discussions with JCCI, it appears the best way would be to start services in the centre of town where JCCI has the highest membership. There, a system of emptying out pits block-by-block in a systematic manner against payment of a modest (approx. 1 USD), monthly tariff would be suitable. In this way every household would have their pit regularly emptied every 3 to 5 years, before it overflows and becomes a nuisance. Additionally, any other customer requiring the service can call-in when needed and pay a one-time fee of approximately 50 USD. To get started, we have supported JCCI to procure a 2m3 desludging tanker that will be attached to their tractor and can easily manoeuvre the steep mountain roads. The sludge will be emptied into a 5m3 mobile tanker that will be parked in one place and will be hauled to the disposal site once a day.

Challenges yet to overcome include working with the municipality to identify suitable land for disposal. We are advocating for the use of a trenching methodology through which sludge can be disposed, subsequently covered up, and planted with trees. A year ago, tackling the problem of establishing a system for safe faecal sludge management in Jumla appeared as big as the mountain peaks all around. Now, with an entity in the lead to establish services that benefit the public, an encouraged municipality, and technical and social data available to inform development of the business model and enforcement strategies, the challenge appears less daunting!

Browse a series of photos from the World Toilet Day celebrations in Nepal.