Explainer: Can a systems approach reinforce locally led resilience in the Sahel?

Climate change is making rainfall patterns extremely erratic worldwide, with dire consequences. One of the starkest examples of this phenomenon was witnessed in Western and Central Africa last year. Torrential rains caused heavy floods, which battered the region, resulting in the deaths of over 1000 people and the destruction of hundreds of thousands of homes. Nearly a million people were displaced by the floods, and many, many more were affected. The destruction was particularly significant in the Sahel region, a semi-arid belt that runs horizontally across the African continent, and below the Sahara desert. In Niger, which lies in the central Sahel, more than 265 were reported dead. In its western neighbour, Mali, the floods claimed dozens of lives.

Floods wipe out hectares of cropland and livestock. In a region heavily reliant on agriculture and already plagued by prolonged droughts and desertification, such shock events lead to severe food insecurity. Rising temperatures—in central Sahel, temperatures are increasing 1.5 times faster than the rest of the world—affect crop yields and contribute to the crisis. Food insecurity is exacerbated by political instability, which undermines governance and delivery of essential services, and conflict, which is often triggered or intensified due to climate change-induced resource scarcity and heightened competition. As a result, 10 million people in the region suffer from acute hunger.

The crisis is embedded within a web of interconnected problems that tend to feed off one another. In these increasingly complex and evolving situations, traditional development often falls short of achieving their objectives. Agriculture-led growth alone will not be sufficient to address food insecurity, which stems from the combined effects of climate change, conflict, displacement, poverty, and political instability.

The challenge demands a more holistic and systemic approach, particularly as funding priorities shift towards defence and domestic agendas. This is where systems transformation becomes a vital pathway, more important perhaps than ever before, in realising the goals for sustainable and equitable development outcomes.

What is systems transformation?

Systems transformation is about addressing structural barriers in the system to make development outcomes more holistic, sustainable and inclusive. For instance, in the case of food security, among the more traditional approaches would be the distribution of food packets. However, a systems transformation approach would focus on inculcating practices that improve soil health, enhance water resource management, inform policy infrastructure design and implementation, and reduce agriculture's environmental footprint. These changes may be small and gradual, but they are strategic and persistent, and tend to have a cumulative effect, eventually marking a fundamental change in the system. These long-term shifts also make development efforts more sustainable.

The systems transformation approach strikes at the root causes of poverty, rather than its symptoms. By the same token, it begins with listening. It involves engaging with local communities and contexts, understanding their needs, power dynamics, and the existing structural barriers within these communities and contexts. It is followed by co-designing interventions with the communities and pulling multiple change levers to work towards catalysing collaboration and enabling local partners to lead the change they are aiming for. A key feature of the approach is constantly monitoring, reflecting, and adapting the strategy to make sure interventions remain relevant to rapidly evolving contexts.

While considering programming, this strategy keeps six dimensions in view: policies, practices, resource flows, relationships and connections, power dynamics and social norms, and values and attitudes. Initiatives carefully consider all dimensions and then work with a combination of those that carry the highest relevance in the context.

How can a systems approach look like in the Sahel?

A case in point is the Agri-Food Programme for Integrated Resilience and Economic Development (Pro-ARIDES). The ten-year programme aims to transform systems by increasing food security, resilience, and incomes in the Sahel region, with a focus on Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Overall, it leverages opportunities in agriculture to improve natural resource and land management, supports the empowerment of youth and women, and contributes to the establishment of effective, decentralised institutions for better service delivery.

Using a holistic approach, Pro-ARIDES works across multiple dimensions of systems transformation, directly targeting policies, practices, and resource flows. For instance, an “onion conservation house” managed by female farmers was built in Burkina Faso’s Nebia village, which faced the challenge of conserving and marketing onions. The adoption of this innovative practice creates opportunities for women to increase their income while improving household food and nutrition security. The programme also promotes local foods through nutritional advice aimed at shifting consumption habits. Together, these initiatives stimulate the market for local food and strengthen its value chains.

Regarding resource flows, Pro-ARIDES operates social and financial inclusion initiatives in the three countries. These initiatives significantly help women and young people, who often face barriers in securing loans from banks and other financial institutions. Savings groups, such as Village Savings and Credit Associations (VSCAs), play a pivotal role in advancing financial inclusion.

A critical part of Pro-ARIDES has been to establish relationships and connections across the spectrum. In this context, the programme strengthens multi-stakeholder governance platforms for land and resource management, synergy between community activities, and cooperation among value chain actors. Pro-ARIDES supports citizen participation in governance, working towards equal distribution of power and voice, through initiatives such as capacity building, resource mobilisation and accountability frameworks.

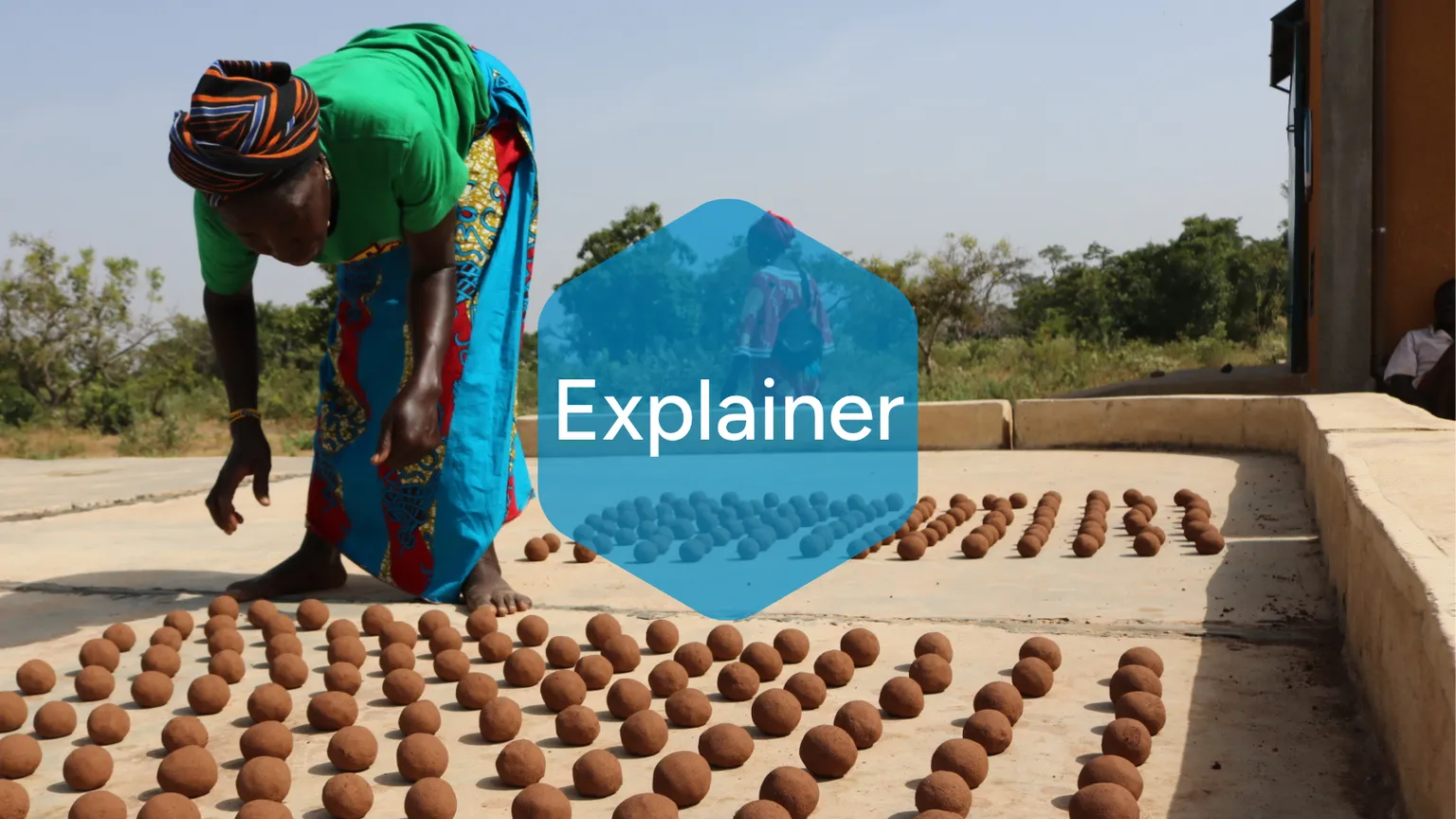

Women in in the commune of Kyon in Burkina Faso carry millet in basins during harvest.

Can a systems approach address challenges of governance in fragile contexts?

Another example of systemic governance transformation is the Accountable Local Governance Programme (PGLR+) in Mali, funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and implemented by SNV (Lead), Oxfam Novib, the V4T Foundation, and Cordaid. The programme seeks to restore and reinforce the social contract between local authorities and citizens, with a strong emphasis on youth and women as agents of change.

PGLR+ works across multiple dimensions of systems transformation. It cultivates new practices by embedding youth leadership in local governance and fostering recognition of young citizens as legitimate partners. It reshapes resource flows by promoting youth- and gender-sensitive budgeting processes. It strengthens relationships by creating inclusive dialogue between youth and local authorities, while at the same time consolidating networks among youth-led organisations. Through training, mentorship, and advocacy, the programme also rebalances local power dynamics, challenging entrenched hierarchies and empowering young men and women to claim a voice in decision-making.

Finally, PGLR+ challenges harmful social and gender norms that limit participation and advances policy reforms that anchor accountability, transparency, and inclusiveness within local institutions. By addressing practices, resources, relationships, power, norms, and policies in tandem, the programme is demonstrating how inclusive governance can shift systems in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Challenges across the Sahel—climate shocks, food insecurity, and political instability—are deeply interconnected and cannot be addressed in isolation. They demand systemic, context-specific, and locally led approaches that generate gradual but strategic shifts across multiple dimensions of society. Over time, these shifts reinforce one another, tackling the root causes of fragility and laying the foundations for development that is both more sustainable and more inclusive.

Sustainable systems transformation can only be achieved when those we aim to serve are not just beneficiaries, but active actors—fully engaged and influencing every stage of the process.

Freddy Sahinguvu, Programme Lead for PGLR+

Find out more about systems transformation

Systems transformation lies at the core of our 2030 Strategy and has remained central to our work over the past year. Across our programmes, we are committed to influencing and positively contributing to shaping policies, practices, resource flows, social norms, values, behaviours, and relationships.