How business-as-usual approaches do women a disservice

COVID-19 has heightened the vulnerability of women to socio-economic shocks. Women’s paid labour and women-led businesses are under immense pressure. Women’s care work has increased due to quarantine measures and home-schooling – both in industrialised and developing contexts. UN Women warns of a roll-back in women’s economic gains due to the coronavirus. If we want everyone to benefit equitably from COVID-19 recovery and responses, we must do better. We must act deliberately.

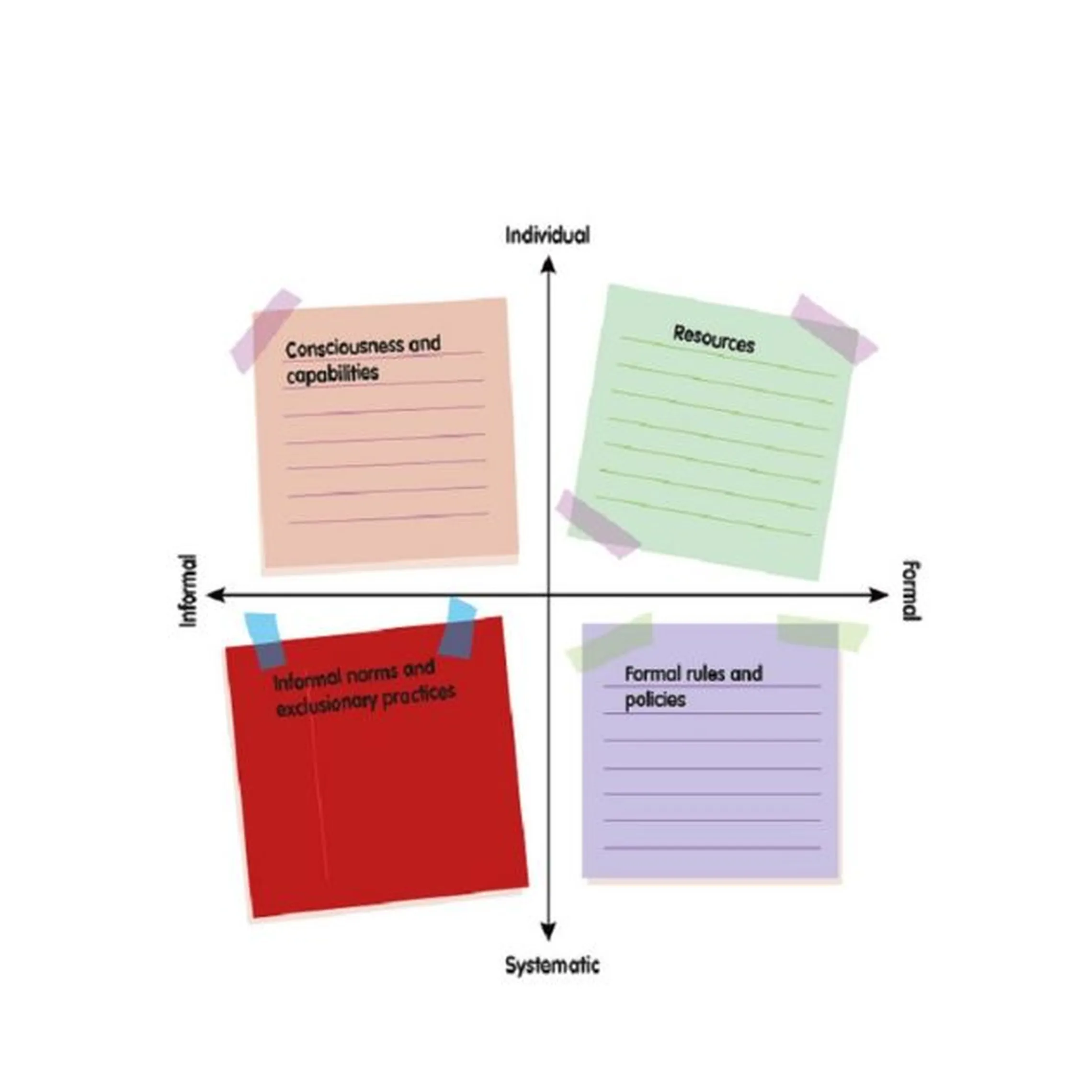

The Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) sector has a clear role to play in economic recovery from COVID-19. The sector acts as an employer, economic activity stimulator, and offers a mechanism to achieve safer, healthier, and more productive workplaces. With the private sector, SNV has been fine tuning its approach to WASH private sector development. Over the years, we have been promoting new economic activities, facilitating inclusive entrepreneurship opportunities, and strengthening women's leadership role (and voice) in existing WASH businesses. To keep us on track, we have been using the Gender@Work framework to map emerging enablers and barriers to women’s entrepreneurship and empowerment, and inform our approaches going forward.

Learn more about the Gender@Work framework here

Pitfalls of a single-minded focus on economic empowerment

As part of SNV’s ongoing gender equality and social inclusion work, our Bhutan, Lao PDR, and Nepal teams have been embarking on diverse journeys to promote women’s entrepreneurship.

Applying the Gender@Work framework, country results have been varied. Strikingly, a commonality across all countries has been the recognition that training women and increasing women’s access to opportunities do not always raise women entrepreneurs' status. Nor do these activities automatically guarantee economic success. These findings validate that economic empowerment activities alone are incapable of transforming gender relations at home, in communities, markets, and public sector. SNV’s findings echo the results of a study by the Institute of Sustainable Futures in the University of Technology Sydney on WASH enterprises in Cambodia. The study found that women's capabilities to grow their businesses have been hampered by their care work responsibilities, mobility restrictions, and time availability for business activities.

Mixed-gender sensitivity trainings insufficient

In Bhutan, SNV has been growing the labour market for rural women by facilitating their participation in masonry – a job traditionally held by men. Experience in Bhutan demonstrated that mixed gender sensitivity training participated in by potential women masons and their husbands did not lead to transformative change. Social conventions that limit the mobility of women masons have discouraged them from travelling outside their village. Because women had to operate within a small market, business development opportunities were minimal. At community level, a woman mason stated that ‘community members don’t think we [women] are as good as the men.’ As a result, demand and opportunities for women masonry work died off as quickly as their husbands started reinforcing the social norm of not supporting their greater mobility.

Mapped against the Gender@Work framework, SNV has recalibrated its approach to women’s economic empowerment in Bhutan. Going forward, responses will address both norms and exclusionary practices and women’s consciousness and capabilities. A range of strategies is being explored in relation to mobility, shared travel opportunities, cooperative models, and increasing community leadership support and incentives.

Click to download 6-page practice brief

Business development hampered by gendered norms and limited resources

In Nepal, SNV has had some success in diversifying the sanitation and hygiene product offerings of women WASH entrepreneurs. In some cases, SNV’s support has led to the scale-up of women’s businesses; from mobile-only businesses to shop ownership. A recent survey of women entrepreneurs in the districts of Sarlahi and Dailekh highlighted, however, that business decisions are often controlled by their husbands. For Sarlahi’s women, their ability to expand their business is limited by their care work responsibilities. Poor transport combined with mobility restrictions and limited confidence to sell to strangers kept Dailekh’s women from investing significant time in their businesses. Poor access to suppliers of raw materials was a shared challenge across the districts.

Mapped against the Gender@Work framework, these barriers relate to resources, informal norms and exclusionary practices, and consciousness/capabilities. Responses being tested to date include linking up suppliers, creating support structures to engage relevant family members to share in the pressures of care work, encouraging joint decision-making regarding income and business management, and supporting women’s leadership.

Deliberate actions for transformative change

The Gender@Work framework has been effective in informing our teams’ next steps to progress women entrepreneurship initiatives. Our practical experience tells us that we need to do more to ensure that progress achieved is transformative and may be sustained. In this case, taking deliberate action in women’s economic empowerment means implementing feminist economic responses that balance the gendered effects and interactions between paid and unpaid sectors of economies. By doing so, we transform societies and make the world better equipped to respond to crises situations in ways that responses and recovery efforts are shared equitably.

Authors: Gabrielle Halcrow with Claire Rowland

Note: Reflections and lessons outlined here and in the practice brief are part of an ongoing SNV partnership with the Australian Government's Water for Women Fund, which is being implemented in Bhutan, Lao PDR, and Nepal.

Photo: SNV staff dialogue with sanitation entrepreneurs in Savannakhet Province in Lao PDR.