Making the invisible visible: The hidden risks of traditional cooking

In a rural Cambodian kitchen, the crackle of firewood blends with the aromas of rice and grilled fish. Mrs Chak Sophal, a mother of three, leans over her ceramic stove, fanning the flames as smoke drifts through the room. Unseen in the haze are microscopic particles, known as PM2.5, that penetrate deep into her lungs with every breath. For families like Sophal’s, this danger is invisible, abstract, and difficult to understand—until it is translated into something more tangible.

Making the invisible visible

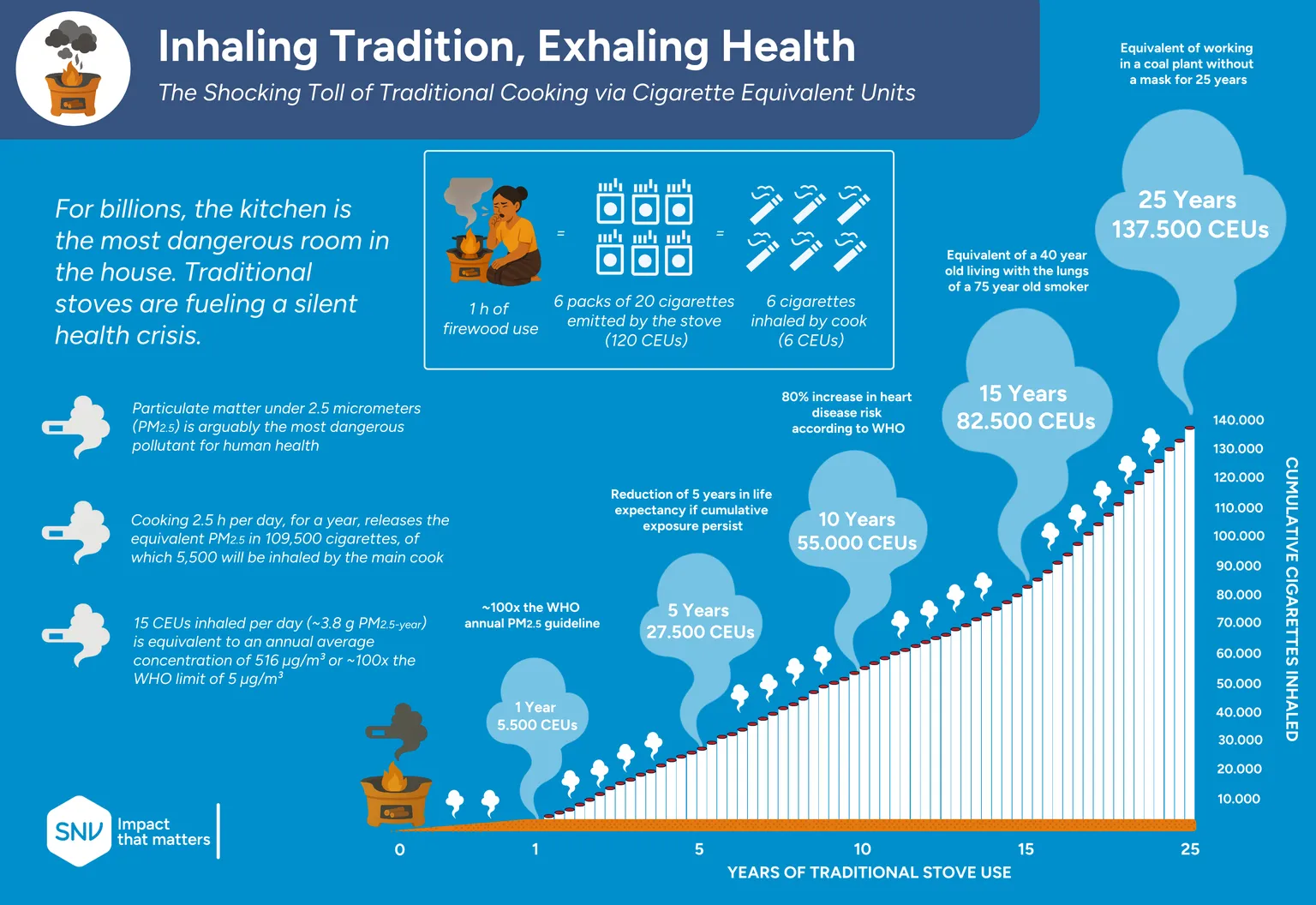

How do you explain that the air in a kitchen can be as harmful as smoking cigarettes? Through its Smoke-Free Village initiative, SNV in Cambodia partnered with the Biomass Energy Lab at the Institute of Technology of Cambodia (ITC) to find a solution. Building on earlier research conducted by SNV in Vietnam, the team developed a metric known as Cigarette Equivalent Units (CEUs). The idea is simple: translate smoke exposure into cigarette equivalents—something anyone can imagine.

At ITC’s lab, researchers recreated a cooking environment by burning firewood in a ceramic stove and measured the total fine particles (PM2.5) released in micrograms. They then compared this with the PM2.5 emissions from burning cigarettes.

The findings were striking. A ceramic wood stove was found to produce up to 1,600 milligrams of PM2.5 per hour, compared to just 13.7 milligrams from a single cigarette. Put simply, spending an hour cooking on a wood stove can expose someone to the same level of fine particles as smoking around 120 cigarettes.

For Sophal, who spends around 2.5 hours a day cooking, her daily exposure equals nearly 300 cigarettes—of which she probably inhales the equivalent of 15 cigarettes. These findings confirm earlier results from Vietnam and highlight the urgent need for behavioural change in cooking habits.

Accumulating damage

Over the years, this invisible exposure builds up in the body, increasing the risk of chronic respiratory illness, heart disease, and reduced life expectancy. Women and children, who spend the most time near cooking fires, are most affected. Globally, household air pollution from solid fuels remains one of the leading causes of premature death.

To make these dangers easier to grasp, the team developed an infographic that translates smoke exposure into cigarette equivalents. By comparing hours spent cooking to cigarettes smoked, the graphic turns an abstract health risk into something everyone can see and understand.

Starting new traditions

CEUs matter because they help distil science into something relatable. But numbers alone do not change habits. Firewood cooking is deeply ingrained in daily life, and for many families, the idea of switching to clean fuels feels unattainable. That is why the Smoke Free Village programme works with local leaders, schools, and health centres to share knowledge and spark dialogue through behaviour change communication. These efforts help communities make informed choices for healthier cooking.

In more than 100,000 households across Smoke Free Villages, social and behavioural change communication has sparked a noticeable shift. Families are cooking with cleaner options, firewood use is declining, and new habits are taking root. What once seemed unreachable is gradually becoming part of daily life, opening the door to healthier homes and stronger communities.