More and better-quality water data

An urgent need for water-insecure parts of the world

Apparently, it’s not as simple as buying into the latest digitalised technology which all too often is gimmicky, not fit-for-purpose, and ultimately abandoned. It is more important that institutions buy into the value of the water data itself for informed decision-making and build an appropriate, functioning data ecosystem. The case of a Kenyan sub-catchment exemplifies how this can work, also presenting some common pitfalls.

As custodian of groundwater and surface water, the Kenya Water Resource Authority (WRA) has a mandate to safeguard water quality and quantity and regulate water use via a permitting system and environmental monitoring. Hosting a population of 65,000 domestic water users and widespread small and large-scale irrigation the Naromoru catchment (a sub-catchment of the Ewaso Ngiro North catchment) is challenged by ever-increasing demands and competition for water.

Across the Horn of Africa, the rainy seasons have failed six times in a row in what is being described as the worst drought in 40 years.

https://www.unhcr.org/news/horn-africa-drought-enters-sixth-failed-rainy-season-unhcr-calls-urgent-assistance

Drought, water stress, and business-as-usual

In the local WRA office, the table is piled high with applications for water abstraction permits. Demand is at an all-time high and continues to grow.

Despite the severity of the drought, the permitting process remains unchanged with assessments of water resource availability based on environmental conditions in regulations from 2007.

Meanwhile, Water Resource User Associations (WRUAs) do their best to allocate water between users when levels drop, mitigating the conflict that arises during water shortages. However, this is becoming more difficult as the changing climate disrupts the traditional system and competitive demands for water continue to increase.

Data ‘steers the course’

In a world where evidence-based decisions steer the course of progress, good quality, fit-for-purpose data, and information are key to creating a robust water system. In Naromoru, multiple actors are involved in collecting and sharing data, which brings benefits, but also some problems.

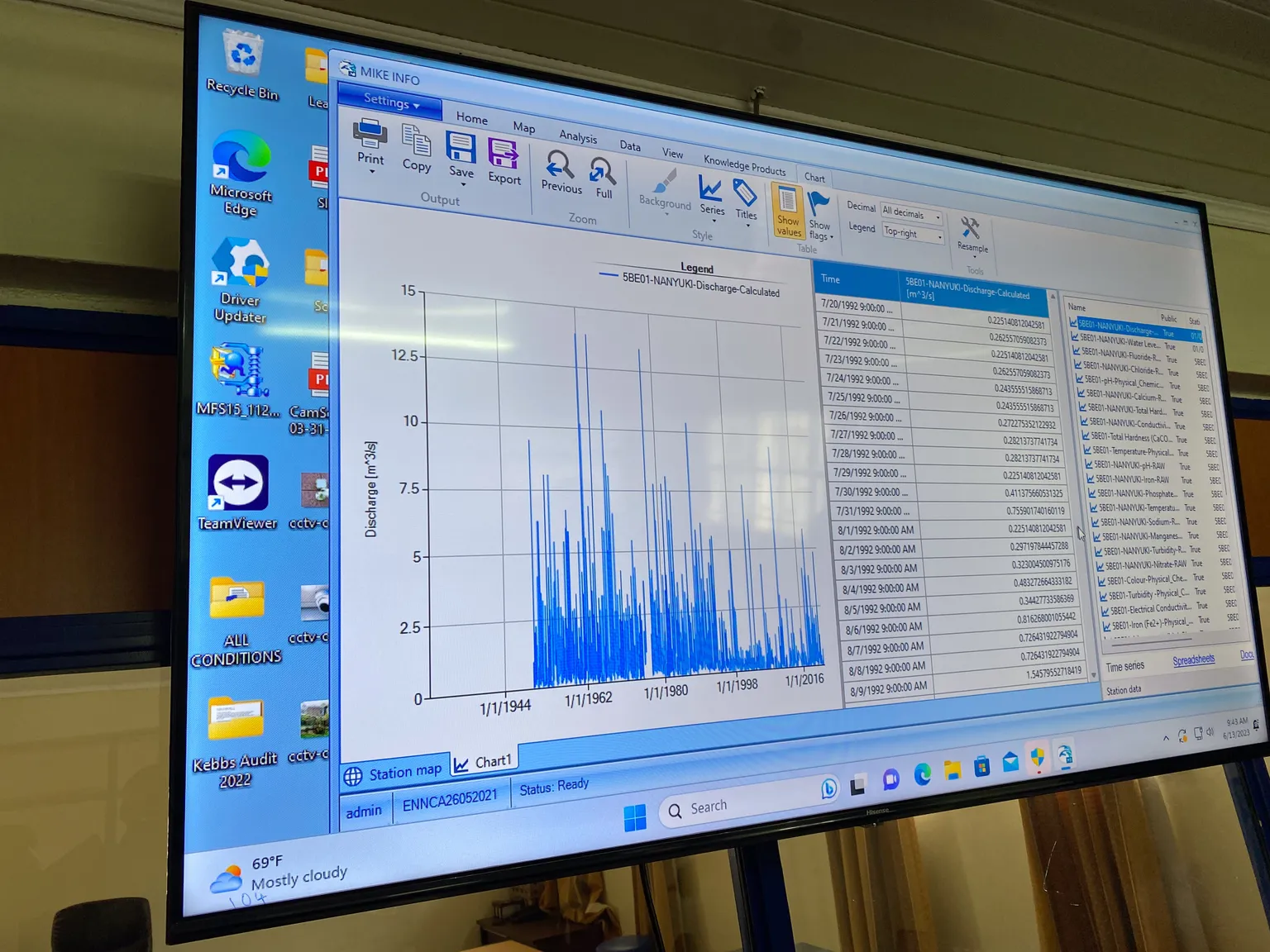

Using its own hydrometric network, the WRA gathers data on groundwater and surface water, storing and analysing these using a MIKE Info system. The WRA collaborates with the WRUA to collect water abstraction data, which are used to calculate abstraction charges and WRUA membership fees. Collected fees finance the WRA and small-scale investment in irrigation schemes. Processed surface flow and groundwater data are publicly available for a fee payable to the WRA. WRUA members can request these data free of charge, in recognition of their role in gathering the raw data.

In addition to the WRA is the Centre for Training and Integrated Research in ASAL[1] Development (CETRAD), a bilateral partnership between the governments of Kenya and Switzerland. It has a research mandate and gathers hydrological and meteorological data from its own hydrometric network to ‘assess and evaluate the potential and utilisation of resources in arid and semi-arid lands.’

Relationships between WRUA, WRA, CETRAD, and other government departments, such as the Kenya Department of Meteorology, are good. There’s an agreed understanding that sharing data is beneficial, but its practicalities can still be problematic.

Data and information systems inhibit progress

CETRAD makes its data available upon request, as does the WRA (for a fee to non-WRUA members). However, both say that requests for data access and exchange are minimal.

From an overall perspective, current practice is inefficient. The WRUA which represents water users would like it to be easier to access data and information that meet their needs, especially for managing water during dry periods.

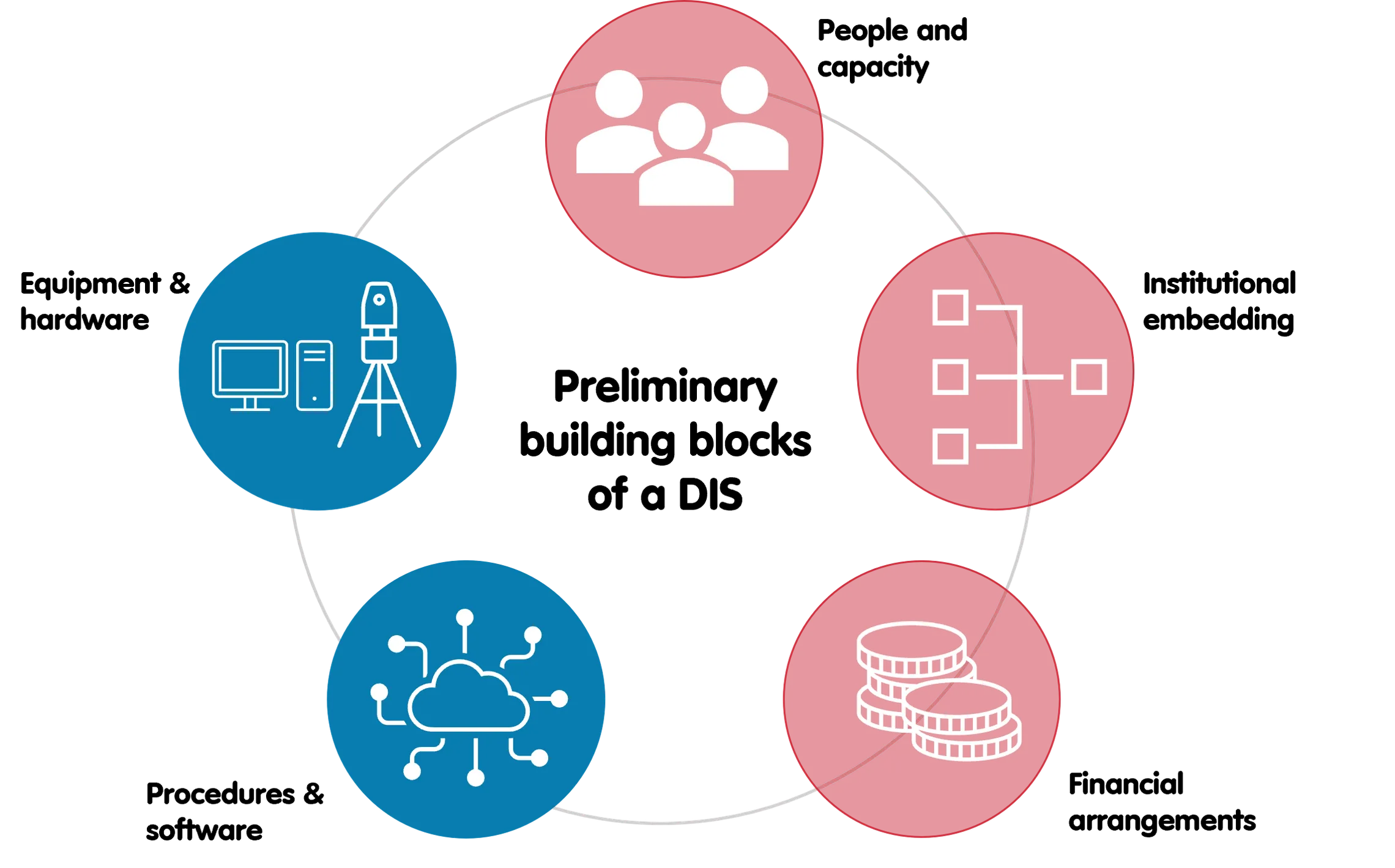

All those involved agree that democratising water data will help to manage water better. Much of the focus, however, has been on improving the technology side of Data and Information Systems (DIS), often excluding or not paying sufficient attention to 60% of the problem.

Barriers to democratising data include:

A lack of data in the first place, e.g., the absence of long-time series hydrological data. Not prioritising water data can lead to inadequate monitoring budgets, subsequent data gaps, or other poor-quality data.

Project-centric data systems have made organising and transferring data more difficult.[2] WRA uses MIKE Info and CETRAD uses the Social Hydrological Information Platform (SHIP) for data storage and analyses. Meanwhile, WRUA groups rely on paper-based and independent Excel systems. Previous attempts to improve data collation and management using inappropriate technology systems have either failed to deliver what is needed or have become obsolete and/or abandoned.

This network of actors is still grappling with the challenges of sharing raw data with its inherent data anomalies (such as from faulty monitoring equipment) on one side versus processed (cleaned) and analysed data on the other. There is a fine line that separates ‘analysed data’ and ‘information’, and agreeing on what people really need and what should be transparently available is an ongoing challenge.

Clearly, a techno centric DIS response alone is not the panacea to advancing progress in monitoring water systems. Equal attention is needed in exploring arrangements that enable (i) people to manage and use the information, (ii) institutional processes and safeguards that are transparent and accountable, and (iii) financial arrangements capable of sustaining operations.

Unlocking the life-changing impacts of data

Using data to update the assessment of water resource availability at the catchment scale and using this to adapt the water abstraction licensing process to correct or avoid over-abstraction would be advantageous for both people and the ecosystem.

During periods of low water availability WRUAs ration water between members through negotiation, usually without much external information on the wider water resource situation or other abstractors’ behaviour. Adjustments in how data is managed and shared could help the WRUA manage water rationing even better.

Measures to better facilitate data sharing and equitable access to data and information include:

Agree on data outputs and formats that meet WRUA needs and help them understand the implications of trends and anomalies.

Normalise routine data sharing rather than ad-hoc on-demand practice.

Use routine data sharing to motivate WRUAs to gather higher-quality water use data. While different organisations typically need their own data systems to meet their own mandates, options to coordinate data collation and shareable outputs could be beneficial.

Measures to optimise the use of data include:

Improve the quality of the data collected by widening the scope of groundwater monitoring and data analysis and getting more detailed information on irrigation water use.

Deepen analysis of water resource assessment and water demand to better inform water-related policies and guide the development of climate adaptation plans.

Measures to sustain improvements in data quality and availability include:

Ringfence national or local government budget for data collection, analysis, and storage to facilitate a sustained monitoring approach.

Be cautiously optimistic when investing in new DIS and storage technologies. Examine them in terms of their ability to expand on and incorporate historical data to facilitate time series analysis.

Notes

Arid and semi-arid lands

Frequent institutional restructuring leading to unclear responsibilities, reduced budgets, and monitoring breakdowns compound issues of sharing and sustainable use.

Interested to learn more?

This blog features key reflections on Digital and Information Systems (DIS) arising from an SNV-organised learning event on equitable water resource management (EWRM).

Contact Sandra Ryan SNV's Global Technical Advisor, Hydrology, and/or learn more about what we mean by EWRM.