Results are in: mapping the water supply in Chum Kiri

Welcome to the latest of a series of blogs on Water Supply Mapping (WSM) as part of SNV’s Functionality of Rural Water Supply Services Programme (FRWS) in Cambodia.

It has been a busy past two months as we’ve worked with our government partners to conduct field data collection throughout all 38 villages in the Chum Kiri district. We conducted duplicate data-entry of all field WSM forms and administered data cleaning and checking, data analysis and mapping. What’s more, we recently held a dissemination workshop to share the findings with our government partners at all levels. Our last blog post covered the training of provincial level government staff on data collection methods and defining f_unctionality_ as the term relates to water supply. This post covers the data and results from the field survey conducted from 3-14 February 2014.

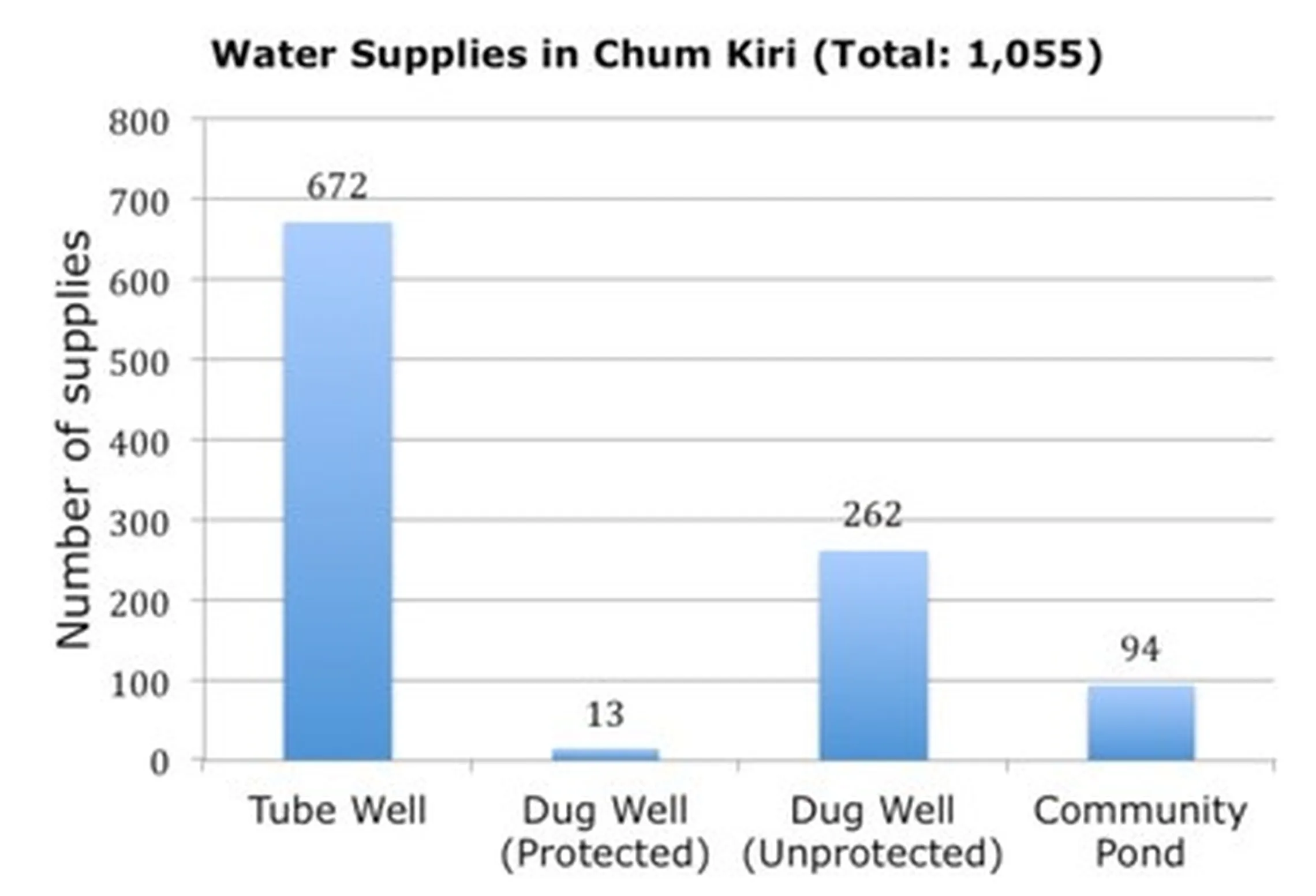

A total of 1,055 water supplies were visited and surveyed, including all of the functioning and non-functioning tube wells (boreholes), dug wells (protected and unprotected), and community ponds in one district of approximately 50,000 people. The survey captured both public and private supplies.

There is a variety of technologically advanced software and hardware options that can be configured to make WSM easier. Some use smartphones and provide capability for: taking photos; marking locations with Global Positioning System (GPS); recording data in an electronic form; automatically syncing data with a central server; and automatically updating data analysis outputs through web-based interfaces or ‘dashboards’.

Early on, we weighed up the advantages and disadvantages of such advanced options. But in the context of our provincial partner and our FRWS programme we ultimately chose to collect data using paper-based forms, enter it manually, and conduct the data analysis and mapping ourselves. In the future, if WSM is applied in Cambodia on a broad scale, the advantages of new technology for streamlined data entry and automatic data analysis will be realized.

Now on to the results of the district-wide WSM survey. The following graph shows the breakdown of water supplies that exist in Chum Kiri District, Kampot Province, Cambodia:

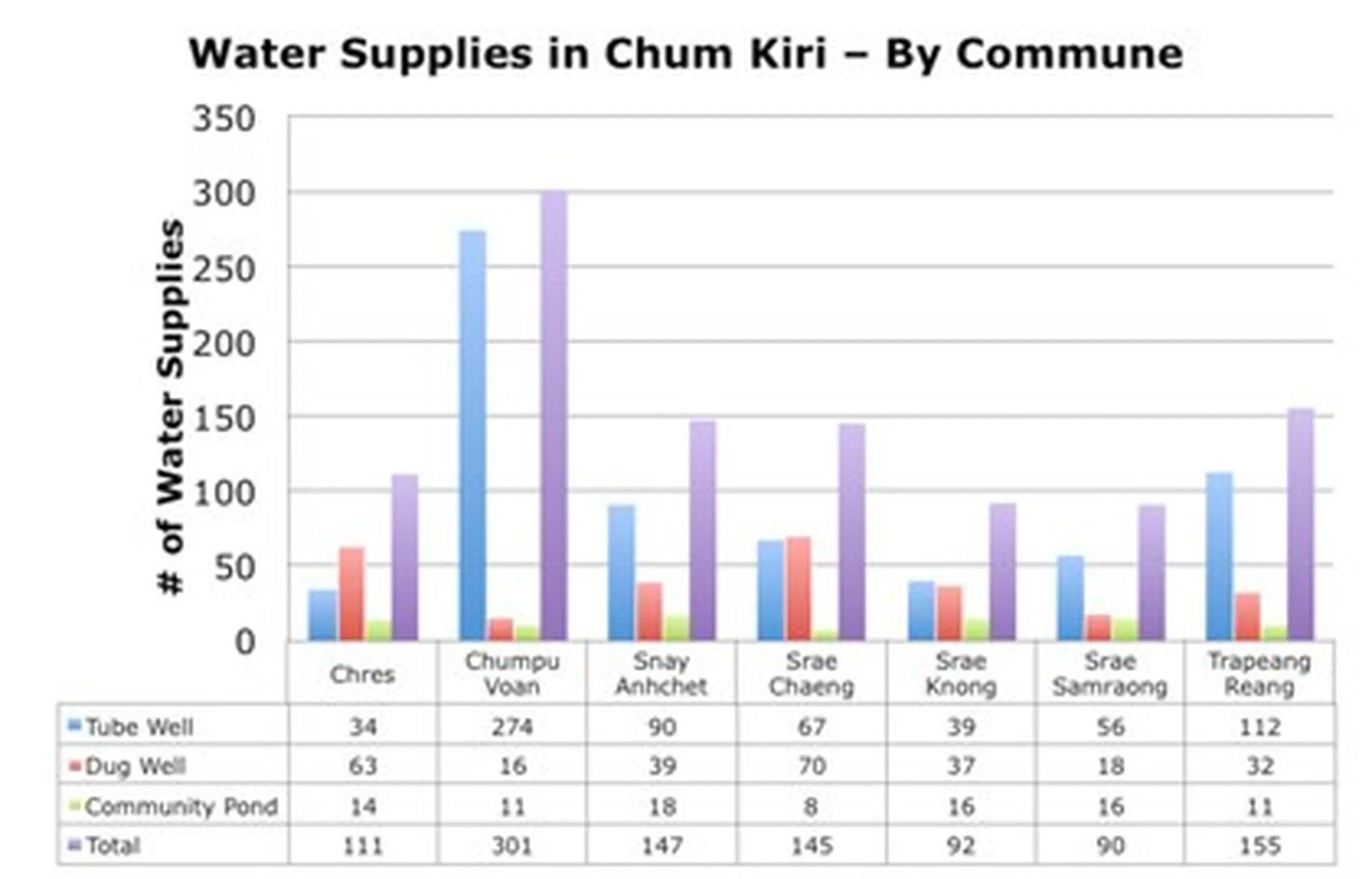

Tube wells were the most common water supply followed by dug wells and community ponds. Among dug wells, the vast majority were found to be unprotected (missing at least one of a cover, lining, or platform). Here is a graph of the types of water supplies in each of the seven communes in our district:

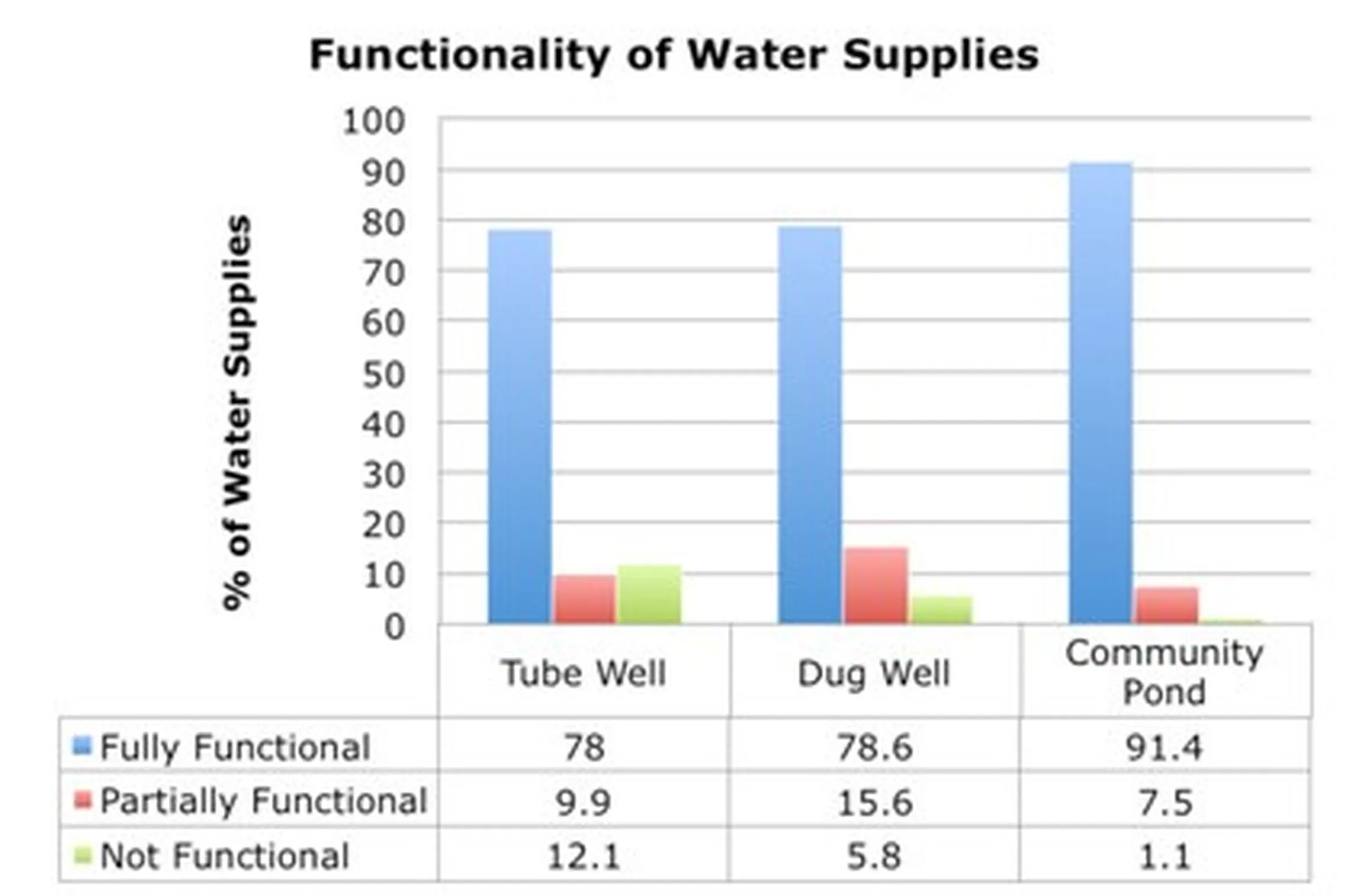

There is a lot of differences between the seven communes. Many tube wells exist in Chumpu Voan, which has a high percentage of all the water supplies in Chum Kiri. Other communes like Chres and Srae Knong have few tube wells but more dug wells. The next graph shows the percentage of water supplies that were found to be functional at the time of visit. Remember that functional was defined as being able to access water as the design of the supply intends.

If water cannot be accessed (for example, because the supply is dried up or because something is broken) then the supply is not functional.

If water can be accessed but it is more difficult than intended (for example, the user struggles to pump water from a well), then the supply is considered partially functional.

Overall, the functionality levels in Chum Kiri were better than expected. Water could not be accessed at all from 12% of tube wells, 6% of dug wells, and 1% community ponds respectively. It is expected that the functionality of dug wells would decrease further in the peak hot season months of March and April when supplies become dried up. This is an issue we learned about from our baseline study last year.

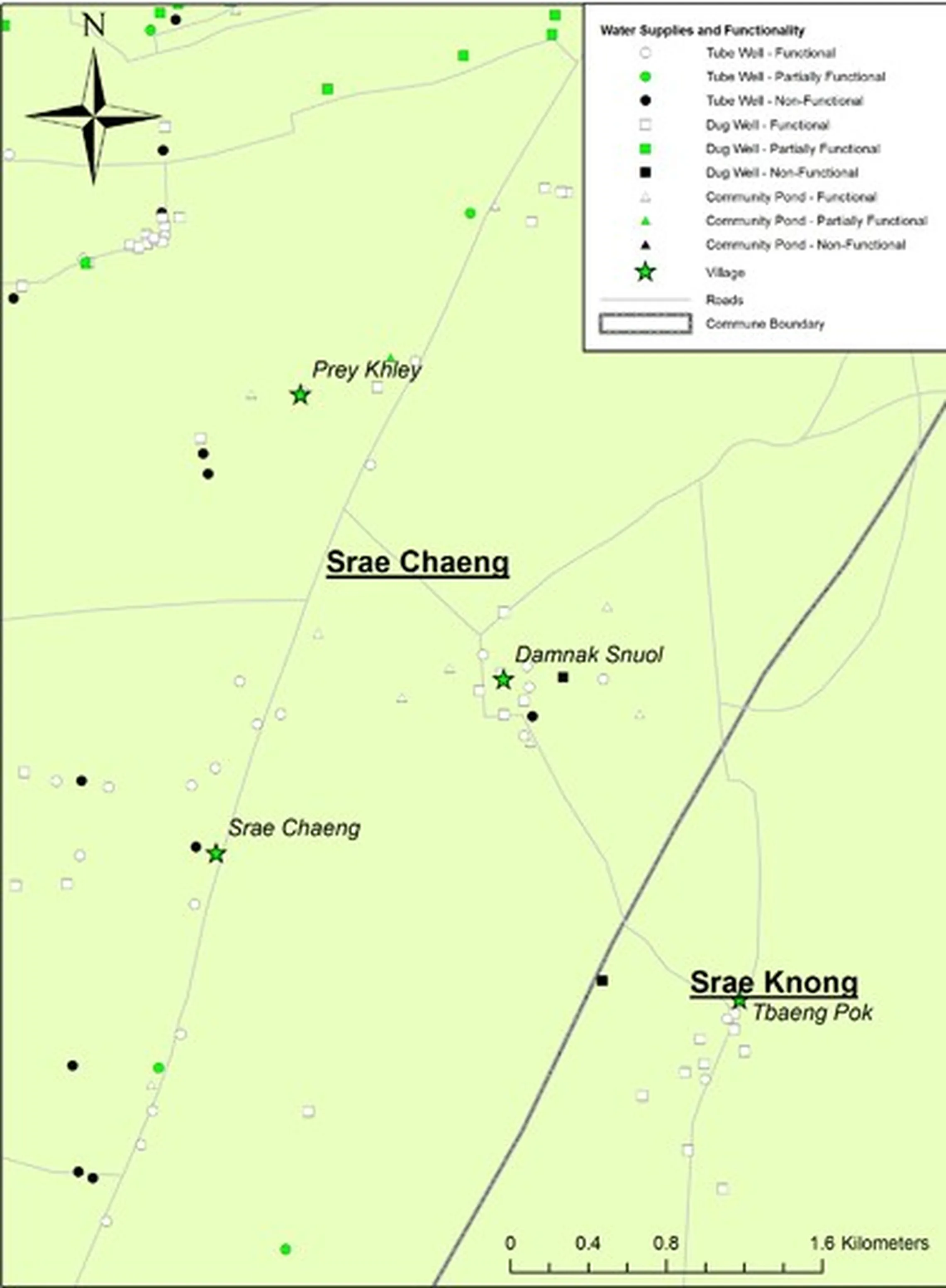

The map below shows an example of how WSM can be used to see where infrastructure exists, which types of supplies are present, and whether those supplies are functional. Such maps will be printed onto posters and used to assist with the creation of Water Supply Functionality Plans during participatory meetings with local government.