Why household methodologies make a difference for gender equality

“Outcome 5: The communities, unions and cooperatives promote women participation and decision-making in horticulture value chains” – I swallowed once or twice as I read the last outcome of the GYEM project that I would manage in Ethiopia. “How are we going to do this?” - That question kept on coming back in my mind, made me insecure, curious and excited at the same time.

Yes, I had done quite a lot of work on gender and had good theoretical knowledge, but this was a daunting task indeed - ‘developing’ women who actively participate in decision-making within three years. The existing situation would not change through a couple of workshops. To be successful, we needed a methodology that would involve both men and women, that would encourage both to discuss how they organise their lives, farming and household work, and most importantly how they decide upon all the little and big things that shape their economic, social and personal life. The Participatory Action Learning for Sustainability (PALS) approach developed by Linda Mayoux, stood out amongst the different methodologies that we considered, as it specifically targets not only women but also men.

Twenty gender champions gathered in Butajira

We started our odyssey in Burajira, the capital of The SNNP (Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’) region in Ethiopia, 110 km of Addis Abeba in November 2016. Butajira is a small city with 33,000 inhabitants, surrounded by fairly fertile agriculture land. Based on government appointments, we invited 10 couples, based on the criteria that they are poor, want to change their situation and can be a role model for their peers – all making them ‘champions’. After their training, the champions would share their goals with others in their cooperatives and villages, using our methodology, building change at the community level.

Twenty champions made plans for change

Using the tools in the PALS approach, men realised that their wives indeed spend a lot of time on reproductive tasks such as fetching water and wood, while at the same time they themselves might be chewing qat (local soft drugs). Women on the other hand realised that they leave many decisions up to their husbands. Some decided they would speak up more. During the workshop it also became apparent that men and women have separate and secret sources of income. They would hide from each other what they earn, what they spend, even where they are and what they do sometimes. In these circumstances, it is impossible to make a family business work and make thoughtful investments. Using the tools in the PALS approach, we could discuss these sensitive issues and couples create a common vision for their household and business.

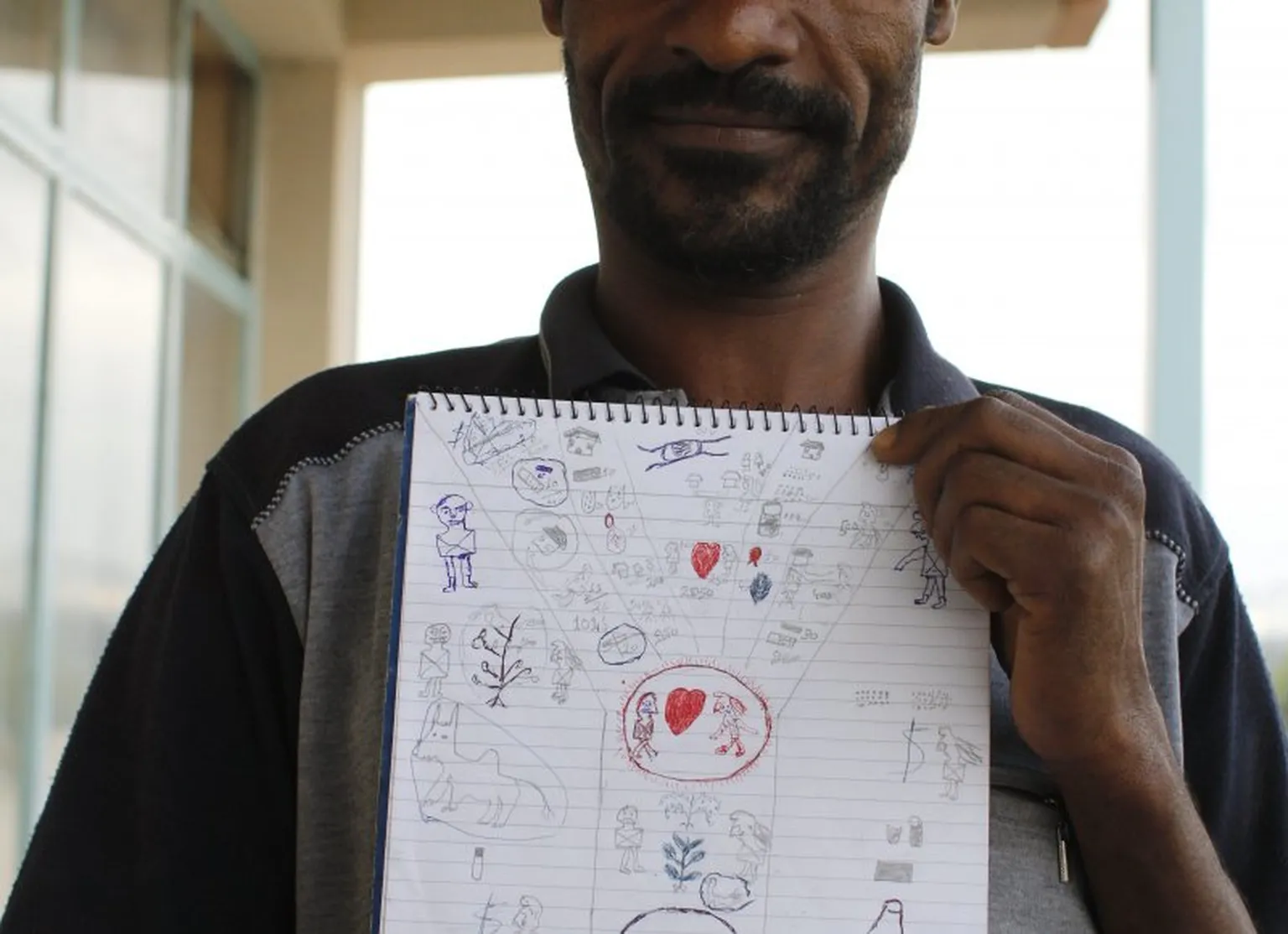

Yasin

Shemege

Two champions shared their plans with me

At the end of a workshop, one man, Yasin, was eager to talk to me. He told me how these two weeks had made him realise what he can change in his own life and how he can manage his time and money better. Without any hesitation he told me the relationship with his wife had been embittered for many years and that his children were suffering the impacts. That he did not see his wife smile anymore, that they were nagging each other constantly and that they did not even sleep in the same bed anymore. During the past few days he had started talking to his wife again and they had discussed putting their beds together again. I felt honoured and ashamed with so much honesty. I could write it down, he told me, and share this with others.

I also spoke to Shemege who was covered from head to toe, only her eyes were visible. She got married at the age of 13, was 25 now and had 4 children with a fifth on the way. “According to the sharia”, she told me, “a women cannot travel far from her home”. Coming to this workshop had not been self-evident for her. In order to convince her husband, she had promised him she would not talk in public and would not raise her hand. This workshop had been the first step for her to open up, speak her mind and discuss with her husband what she can do to increase her economic status if only he would allow her to go out, for instance to the market. Without this first step, change is impossible. Later on, while visiting her, she told me how she had increased her income: she had bought an injera baker and could send her oldest daughter to school in the nearby city with the additional money.

Scaling to achieve our objectives

After the first workshop in November 2016, the programme’s second workshop in March 2017 focused on livelihoods. After the second workshops, the 20 champions each had the responsibility to train four to five peers in their village or cooperative. They also shared their experiences with peers in their saving groups, churches or mosques, reaching 1,161 people and helping to identify 15 new champions, who knew the tools, changed their personal lives and were willing to train others.

When we checked six months later, some men and women were saving €10 per month because men cut spending on alcohol and chat or women were buying less clothes. In other cases joint planning of investments by couples resulted in households being able to build a new house, acquiring new land for horticulture production, purchasing a horse cart to facilitate transport of the crops to the markets, sending their elder children to school in town. Other women joined saving groups, increased savings and diversified their income. It gave them more credit in the community and more confidence in themselves. Some men took up leadership positions in their cooperatives, shared the tools and applied them in cooperative planning exercises. Almost all original champions reported an increased social status in their village.

The final and third workshop in December 2017 focused on preparing the champions to become trainers themselves and upscale their work to other districts. As a result, at the end of the process in June 2018, 16 champion trainers had trained 36 farmers in two additional SNNPR districts, Soddo and Marek. SNV also initiated a new workshop process in the Oromia region. Combined in the SNNPR and Oromia regions there were 33 champion trainers (18 men and 15 women), 130 gender champions, who were trained in the methodology (64 men and 66 women) and 4472 peers were reached in total (50% women and 50% men).

Moving forward, Ethiopia’s Women’s Affairs offices will use tools from the PALS methodology to continue growing and supporting gender champions. The government will build on this critical mass of people to develop an inclusive and gender-transformative agenda.