Confronting the long-overlooked lever for women’s access to agricultural training in conflict-affected Tigray

“I can study knowing my child is safe.”

At Shire Agricultural Technical and Vocational Education and Training (ATVET) college in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, the impact of childcare integration is immediate. For Amleset Giday, the centre meant she could take her COC Level II exam just three days after giving birth, defying local norms that new mothers should rest for a week or more. Her baby was close by, cared for, and safe, allowing her to focus fully on her studies. Her determination and the support of the centre have given her a new perspective: “I want to have my own farm one day,” she says. “This is my chance.”

Haset Berhu’s path was longer. Displaced by conflict, she returned to her studies as a young mother without anyone to care for her son. The centre became her turning point. She drops him off in the morning, visits to breastfeed during breaks, and knows she can study without constant worry.

Before the facility opened, Shishay Moges often had to bring her toddler to class. Disruptions were constant, and fieldwork, essential for hands-on learning, was exhausting with a child in tow. Now, she says, “It’s not just a place for our children. It’s the reason we can learn properly.”

For Askale Amare, whose studies were halted by conflict, returning to complete her Level V diploma seemed impossible with a one-year-old. The childcare centre has made it routine: drop-off in the morning, follow classes, pick-up at day’s end.

I want to have my own farm one day. This is my chance.”

The unseen barrier

These personal accounts highlight one of the most persistent and overlooked barriers facing women in agricultural education: childcare. Without it, young mothers are frequently forced to choose between raising children or completing their education. The result is a cycle, where women’s skills, earning potential, and leadership in rural economies are curtailed before they have a chance to begin.

Tigray endured a two-year conflict that lasted from November 2020 until a peace agreement was signed in November 2022. The fighting displaced more than 2.2 million people at its peak (Reuters) and resulted in severe human rights crises, while public services—including education and agricultural training were disrupted. Rebuilding these systems has become essential, both to restore livelihoods, but also to ensure that women, often most affected by both conflict and care burdens, can participate fully in shaping more resilient rural economies.

Women’s participation in agriculture and in securing sustainable livelihoods depends as much on the systems around them as it does on their skills or ambition. In fragile contexts like Ethiopia’s Tigray region, where conflict has disrupted lives and strained public services, these systems often exclude women in unseen, everyday ways.

In Ethiopia, women are already 17% less likely than men to participate in the labour force, and the gap widens to nearly 29% when education, household responsibilities, and intersecting demographic indicators are factored in. In fragile, conflict-affected contexts, the lack of childcare is more than a personal struggle—it is a structural barrier to equitable progress.

From individual change to institutional reform

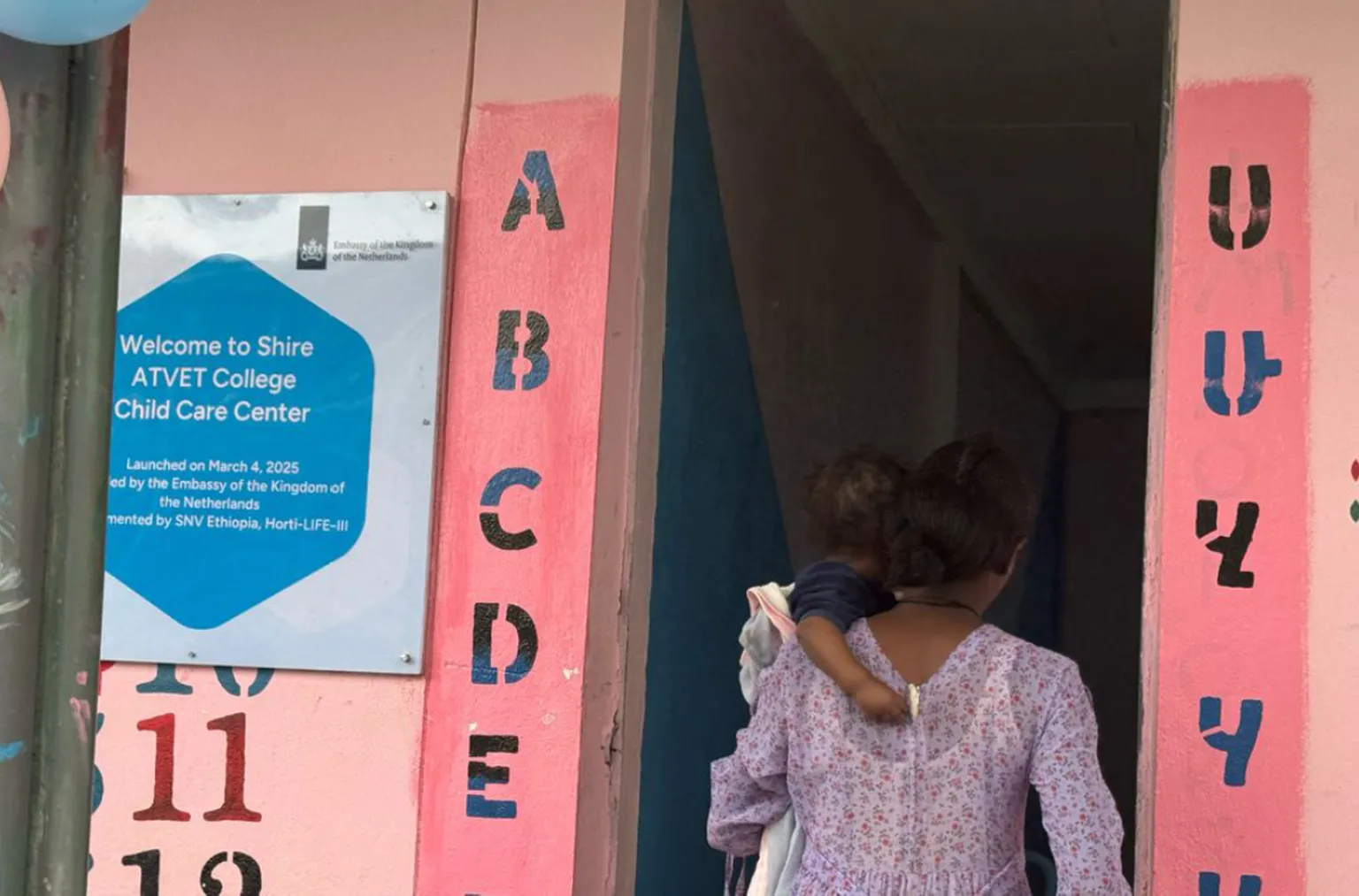

Addressing this requires strengthening the systems that underpin agricultural education and, by extension, resilient food systems. Working with Agricultural Technical and Vocational Education and Training (ATVET) colleges such as Shire ATVET to integrate childcare facilities directly into their colleges offers a simple, effective pathway, a practical and inclusive way forward, implemented under the Horti-LIFE project alongside the Governments of Ethiopia and the Netherlands.

These stories of personal resilience are not isolated incidents. They illustrate how a small structural change, such as the integration of childcare into agricultural colleges, can have a ripple effect throughout the entire education system. By embedding childcare in these colleges, the Horti-LIFE project seeks to redesign the conditions of access to education for farmers, particularly hindered by traditional gender roles, while still enabling sustainable and culturally aligned practices.

This sits alongside other system-level shifts: integrating farmer field schools into the Ministry of Agriculture’s extension system so that participatory, hands-on learning becomes standard; expanding skills-based training to include climate-resilient horticulture that prepares graduates for a changing climate; and strengthening links with the private sector to ensure farmers have access to safe, reliable agro-inputs and markets.

By working with four finance institutions, tailored horticultural loan products were developed to give smallholder farmers access to working capital to procure high-quality agri inputs so they can improve farm productivity.

Together, these initiatives reflect a deliberate move towards systems that recognise and adapt to the realities of the people they serve, particularly women, and position agricultural training as a driver of inclusive rural development.

Scaling what works

By 2029, Horti-LIFE III aims to reach 500,000 smallholder farmers and support 200 agribusinesses. In Shire, the change is already visible today: young mothers attending every class, completing their practical training, and sitting exams on time — all while their children play just a few steps away. Learnings from the initiative have already been embedded in Ethiopia’s new 10-year National Horticulture Strategy, signalling a shift towards systems that are more inclusive, practical, and responsive to farmers’ realities.

Horticulture is one of Ethiopia’s most dynamic agricultural sub-sectors, contributing significantly to export earnings, household incomes, and nutritional diversity. It employs hundreds of thousands of people, with strong potential to create jobs for women and youth in production, processing, and marketing.

By integrating childcare, climate-resilient horticulture, and stronger market linkages into national policy, Ethiopia is not only strengthening a key growth sector, it is using it as a lever for wider food system transformation and inclusive rural development.

As Amleset puts it: “I don’t have to choose anymore.”

As Amleset puts it: I don’t have to choose anymore.”