Perspective: Closing the WASH financing gap

Water is among the world’s most undervalued assets. An efficiency moonshot could turn proven approaches into strategic investments, bringing water into the boardroom.

Nick Tandi, Global Head of Water

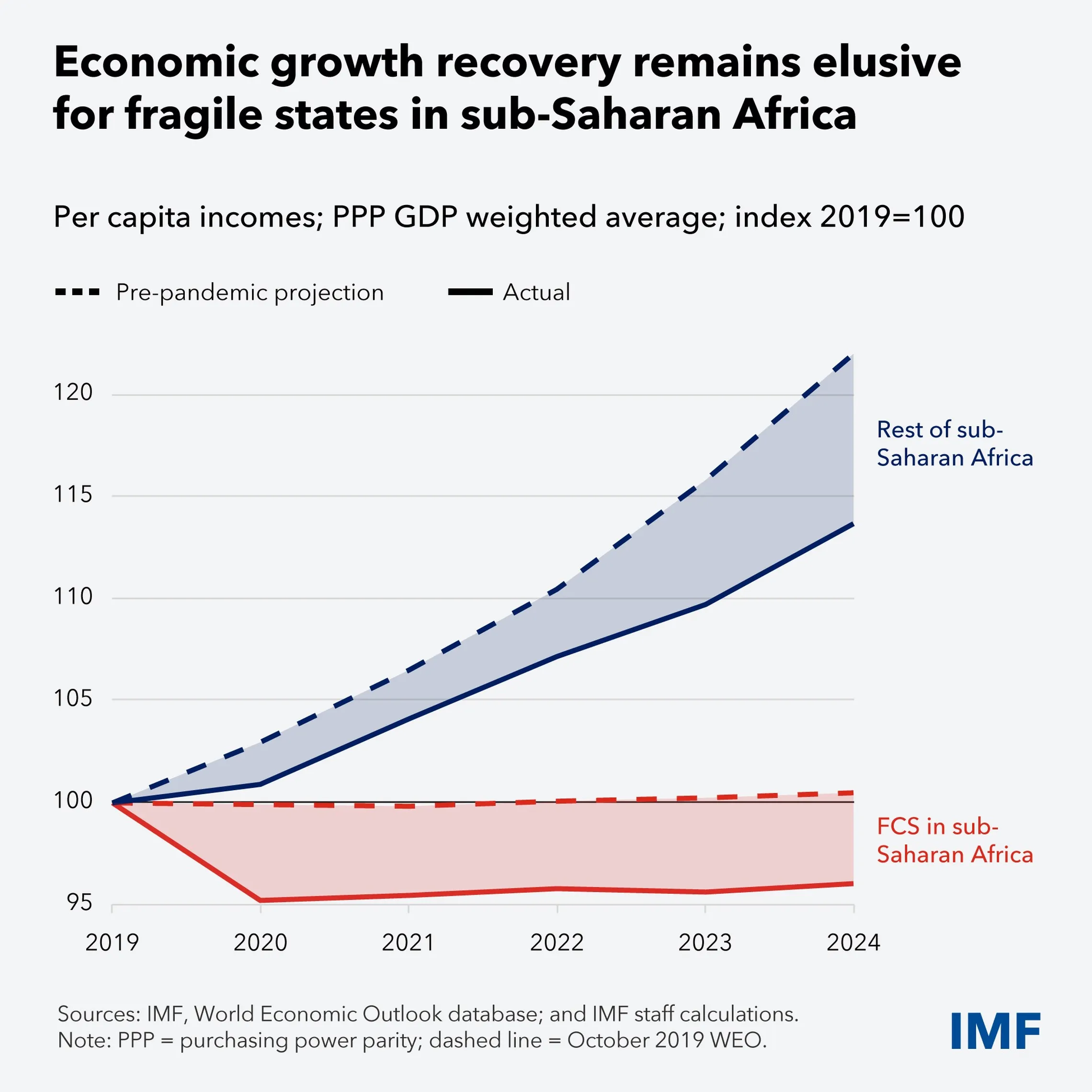

The Water Security Financing Report 2024 by ten multilateral development banks estimates a US$138.0 billion annual spending gap to reach SDG 6: clean water and sanitation. Report findings point out that countries would need to increase annual spending by 2.7-3.0 times globally and in Sub-Saharan Africa, by 9.5-17.0 times. A staggering increase of 42 times is projected for low-income countries facing fragility and conflict.

The scale is massive, to say the least. But the sector is not short of ideas. What we need is an efficiency moonshot at an ambition and scale that can plausibly be achieved.

Over the years, my engagement in the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) sector has shown me that the goal of efficiency is not an abstract aspiration. However, it is a work in progress. Recent evidence from budget execution, cost recovery, and operational performance suggests that in many countries, existing resources have yet to translate into their full potential. For example, on average, budget execution stands at just 72%, and 60% of countries use less than three-quarters of committed domestic capital.

As the sector continues to grapple with challenges in tariff collection, non-revenue water, and operations and maintenance (O&M), this normalised underperformance indicates there is significant scope for improvement to increase the impact of every dollar invested.

Current WASH spending: a reality check

Global GLAAS data show that inflation-adjusted WASH spending per capita has broadly remained stable for over a decade. Across reporting countries, spending averaged US$33 per capita. For lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and low-income countries (LICs), while that spending is currently US$22 per capita and US$12 per capita, respectively, it is a significant share of GDP, at around 1.3%.

It has long been established that WASH systems are funded by three wallets: households (tariffs), governments (taxes), and donors (transfers). On average, households account for about half of reported funding, followed by government at 33%, loans (a financing instrument for repayment) at 14%, and Official Development Assistance (ODA) grants at just 3%. While small in aggregate share, it must be emphasised that ODA remains significant for LMICs and LICs. After all, nearly half of the countries in the GLAAS data report at least one government agency that receives over 25% of its WASH budget from donors.

The overall picture is clear: spending levels are far below what SDG 6 requires, but they seem to have broadly stabilised.

With fiscal space constrained, the question remains whether part of the gap can be closed without spending much more.

The search for more money

There is often an implicit assumption that capital increases for WASH will come from some mix of: reallocation of public financing from other priorities, increased ODA, economic growth, and/or improved sector efficiency. Given recent trends and the three-wallet structure—in which tariffs exceed taxes and taxes exceed transfers—economic growth and efficiency gains appear to be the most plausible short-term levers.

Furthermore, the contribution of growth varies by context. In relatively stable environments, growth can expand household and public resources. In contexts affected by fragility and conflict, growth is often volatile or elusive. Therefore, investments in efficiency gains and service-level prioritisation may be more relevant and impactful.

In environments with relatively greater stability, several approaches have shown promise.

One is engaging private operators as complements to public provision. This requires transparent procurement, public participation, and clarification of contracts, including risk sharing and oversight arrangements. In such models, private operators are incentivised to provide professional service delivery, including O&M, while the government retains responsibility for policy, regulation, and accountability.

Financing for such arrangements remains limited: non-sovereign guaranteed loans and other private-sector financing account for a small share of MDB water approvals in 2024. Whilst these instruments could expand in some contexts, they rely on minimum conditions for regulations, contract enforcement, and public oversight. Where these are absent, gains are more likely to come from improving execution capacity.

Another promising approach combines financial services for households living in poverty (such as a dedicated revolving fund), WASH behaviour change communication, and training for local artisans who construct facilities. This approach can ease household capital investment over time, improve climate-resilient design, create jobs and opportunities, and strengthen O&M so facilities continue to function.

Across multiple contexts (high- and low-growth, stable or fragile), budget execution improvement can often be realised within existing institutional and fiscal constraints.

In practice, this implies that progress may be faster when starting with affordable basic service, while laying the foundations for safely managed ones. From working with partners and counterparts in Nepal and Mozambique, for example, we know that budget execution improves when intergovernmental processes align, and when hands-on technical assistance is provided in the procurement of works. Tariff collection improves when services are reliable: from Bangladesh to Tanzania, we have observed that low-income households and residents are willing to pay for sludge-emptying services they can count on. Functionality improves through area-wide service provision by professional private operators as seen in Uganda and elsewhere.

What the water sector urgently requires is an efficiency moonshot, and we already have a foundation to build upon. Because, for every struggling utility or local government, there is another—in the same country or region—doing much better. Professionals learn best from peers who understand their pain points. This learning and exchange must be scaled.

What this implies

Closing the WASH financing gap will require more resources, but it equally demands greater attention to making efficient use of those that already exist. Though not a replacement for economic growth, public finance, or ODA, an efficiency moonshot is worth pursuing. Without it, the combination of traditional, including new forms of funding and financing mechanisms, will not be sufficient to meet SDG 6 targets.

Crises often open space for reform. We should not waste this moment.

Water strategy is a boardroom priority

Attending the Economist-organised 1st annual Water Summit in London? Catch Nick and peers from the World Bank, EBRD, Climate Impact Partners, and Scottish Water during the panel, Water for Growth: Financing universal access in emerging markets.

Nick Tandi

Global Head of WaterNick Tandi leads the water team at SNV, a global development organisation active in more than 20 countries across Africa and Asia. Over the past two decades, he has held technical advisory roles in water management and climate adaptation, supporting programmes that advise governments, civil society, and companies across much of the developing world. His previous experience includes work with the World Bank and the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI). He has a multidisciplinary training in the natural sciences, social sciences, and development finance.